If you don’t want to read this whole post, there’s a big takeaway for anyone who releases code: Please make sure you have an easy way for people to be notified to a new release.

The Story…

I use WordPress a lot. It’s made me lazy on a lot of things, like version control. It’s also made me incredibly complacent when it comes to updates. You see, WordPress has a massive API system and servers which allow you to get in-app alerts to any needed updates. Click to upgrade and done. It’s second only to Chrome, which just updates.

I use WordPress a lot. It’s made me lazy on a lot of things, like version control. It’s also made me incredibly complacent when it comes to updates. You see, WordPress has a massive API system and servers which allow you to get in-app alerts to any needed updates. Click to upgrade and done. It’s second only to Chrome, which just updates.

Now there are pros and cons about automated updates, and some things, like my server software? Hellz no, son, I don’t auto-upgrade that! Yes, I auto-upgrade cPanel and other server tools that I added on, but PHP and Apache and MySQL? No, those are things I have to stop and make damned sure I know what I’m doing. Why? Because they’re not ‘add on’ software, they’re the core functionality of my entire webserver, and if I mess them up, I am up shit-creek.

If you’d asked me last year ‘Should WordPress auto update itself like Chrome?’ I would have shouted no, very loudly. And now here I am, doing it. Personally I’ve been using Gary’s Automatic Updater on all my sites for months now, because I know my WordPress setup is tight. I love the Chrome and Firefox auto updates, because I don’t customize those things ever. While I do customize the hell out of WordPress, I do it smart and I do it right. My code is doing_it_right() and the plugins or themes I add on to my sites are all well vetted and Elf Approved. The same can’t be said for everyone, but after a lot of thinking, I think if WordPress auto-updated, people would have an initial clamor of pain with all the shitty code out there that broke, and then the bad code would Darwin itself right on out of use.

But that’s not the point of this. In my head there’s a difference between ‘core software’ like PHP, and ‘app software’ like WordPress. The lines are clear, they should never be crossed. Auto-Updating works for apps, not for core. And what happens when your app doesn’t even auto-alert for updates? How do you handle updates?

I’ve already mastered using git as a ‘deployment’ tool, and svn has been old hat for me. That means I know how to quickly update my code, but I need to know when to do this.

The Solutions…

There is a light at the end of the tunnel. There are some easy ways you can keep track and, conversely to the devs, make it easy to keep people up to date, and it all starts with the code’s website. You do have a website for your code, right?

Check the website

If there’s a blog, there’s probably an RSS feed. This is really easy, since most (if not all) blog and CMS tools use RSS.

No RSS? No blog? Maybe there’s a mailing list. This is actually my favorite option. I hate email, but I love getting emails for software updates like that. If that’s not your thing, see if the mailing list has an RSS feed. I know people use Google Groups for a cheap mailing list, and if you visit the Groups page and click on the about link (see the image, not the dropdown, the link), you get a whole mess of RSS options!

No RSS? No blog? Maybe there’s a mailing list. This is actually my favorite option. I hate email, but I love getting emails for software updates like that. If that’s not your thing, see if the mailing list has an RSS feed. I know people use Google Groups for a cheap mailing list, and if you visit the Groups page and click on the about link (see the image, not the dropdown, the link), you get a whole mess of RSS options!

This only works for public groups, but why would a private group be an announcement list for your app releases anyway? If it’s private, get used to email.

Speaking of mailing lists, MailMan, my list of choice, does not have RSS feeds. It’s the old spavined mule of lists, I know, but for people who love it, check out MailMan-to-RSS.(The irony I feel in writing that, which is the opposite of how I handle things with my post2email plugin, is deep and unfathomable.)

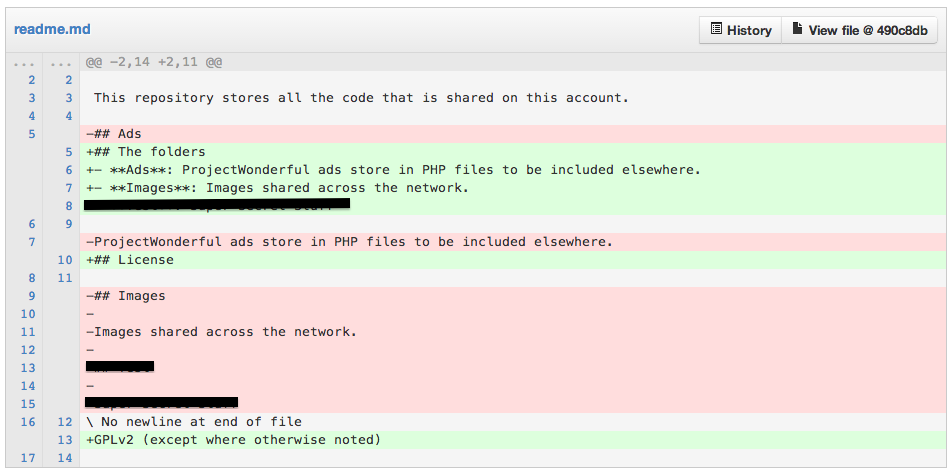

But what about those other guys? You know who I mean, the guys who use GitHub as not just a version control tool but their code host? After all, Github Pages are pretty cool, and free, so why not? Time for a practical example.

My amazing friend Mel made a site for Dashicons. They’re like Genericons for your WP Dashboard, and if you’re using MP6, you’re looking at them now. (Mel pointed out to me she did not make all the icons, only some, but the site is hers, so her I pick on.) The site is awesome. It’s fantastic that people can make sites like that, and you can even put a custom domain on it.

But look at it! No feeds!

Thankfully, Github pages are built on Jekyll, and you can set up feeds. But let’s be frank, if it’s not automatically set up for people, they’re not going to do it. And most people don’t do the ‘blog’ part of their Github page sites either. Now what?

Well thankfully, for anything on GitHub, since most people push releases with tags (note to self…), you can use this for rss: https://github.com/user/project/tags.atom — Sadly, I couldn’t find one for branches.

The Real Answer…

Look, at the end of the day, if you’re releasing public code, it’s incumbent upon you to make a way for your users to be able to find out, easily, when you’ve updated. Expecting them to come to your site and check is not going to work. Making an automated way to push your code, your changelog, and your update notices to people, will put it all in one go for you and make it easy. If, like me, you’re afraid people will end up getting too many alerts, make it a blog post and only do it when you know you’re ready.

Making it easier to get alerts for needed upgrades is going to make everything safer, in the long run. Think of all the security patches people are missing, just because we don’t get notified of them!

Now if you’ll excuse me, I need to sort out how to better use branches and tags.