My father was having email woes, so I undertook the monumental task of sorting out his hellish setup. Among other hurdles, he still uses (and in fact prefers) POP email.

Don't judge him.

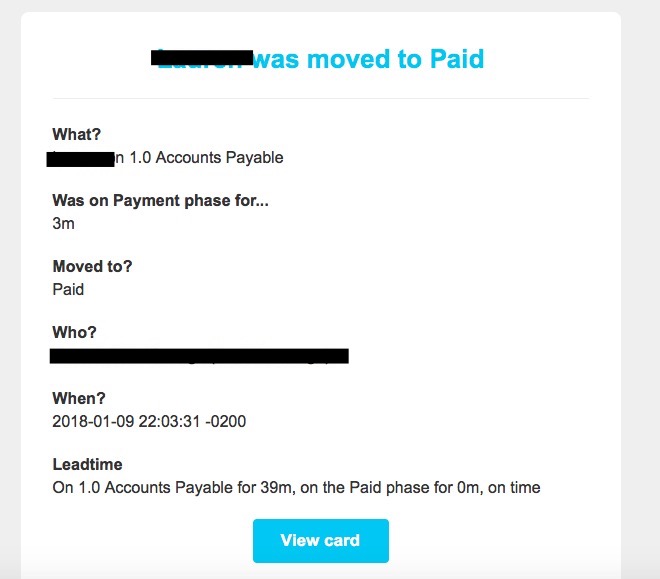

However it was in reviewing the POP mail that I found a problem. He had over 145 emails, and of them only 33 or so were legitimate emails. Of the other 112, about 20 were 'mailing lists' (like Safeway and Egencia and crap we do actually use), 5 or so were porn, and then 87 were from a deployment service.

Not His Monkey House

I double checked that my father didn't use the service and then I looked at the email. They were all emails for an account payable system that he absolutely didn't use.

That's not at all Dad's job, so I agreed they were likely junk but how did they get there?

A Real Company

The first thing I did was check that this was a legit company. Interesting. I then did the logical step and requested a password reset for his email. It emailed me a link, which I clicked and yes, it let me reset the password… Except it didn't.

I got an error saying that the 'username' was already in use.

Which made no sense. I was on the password reset form. Not a create user form. So I tried a few different ways, and then tried to file a bug report or ask for help with is email and it all error'd out. It did not like his email.

To Twitters!

I then complained on Twitter, which netted me the very helpful Isabelle who DM'd me and knew right away what was happening.

The hundreds of emails were actually just a mix-up because one of our product specialists had a demonstration company with a database with tons of 'demonstration users' with personalities and characters names and your dad's email got in by accident (due to its homonym toy story character).

Isabelle

Dad's domain is woody.com you see.

Suddenly it all made sense.

Why We Use Example.com

They went ahead and removed his email from all their pipelines and deleted the fake account they'd made for the domain (which explains why I couldn't do a reset). And I haven't seen an email come in after that.

It was a rude awaking for this poor company. We don't use real domains in our examples for a damn good reason: people copy/pasta.

No one thought to check if the domain existed, and it's pure coincidence that they picked his email for the demos and examples. And yet it's a good reminder for you too. Those example domains you pick will probably be used by someone in production. Don't spam them.

But a bigger concern is this. How much private data got sent to my father over the course of the weeks this was the case? How much information did he have access to that he shouldn't? You're all very lucky he's not malicious.